by Charles Litton, UNeMed | June 6, 2013

Scientists, physicians and major media have long been raising alarms about antibiotic-resistant strains of bacteria, but too few have drilled down deep enough.

Resistant bacteria are certainly bad enough, but it’s not our biggest problem.

What should really keep us awake at night is not the bacteria’s ability to adapt to our countermeasures, but our inability to match their pace.

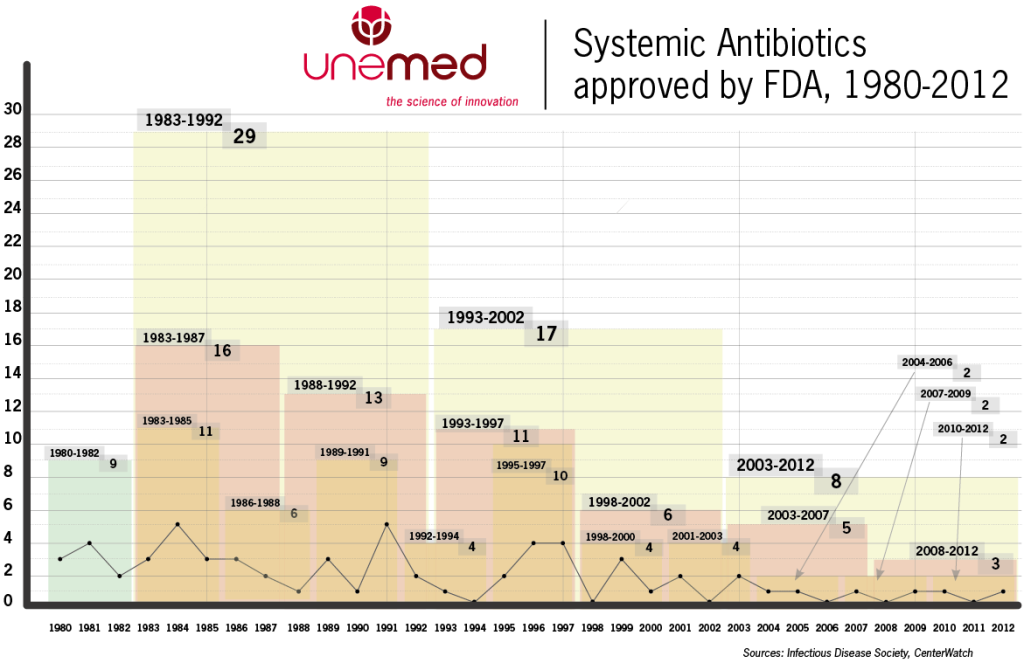

Systemic Antibiotics approved by FDA, 1980-2012

Sources: Infectious Disease Society and Center Watch.

The way things are going, it won’t be long before our marvelous modern medicine may not look or feel so, well, modern.

The antibiotic pipeline is drying up, and there aren’t many pharmaceutical companies working on solutions to so-called “superbugs,” or even average not-so-super bugs for that matter. In the last 10 years, the FDA has approved just eight new antibiotics, or less than half of the 17 that were approved in the previous decade.

At this point it’s tempting to supply some cheeky assurance that it’s not as bad as all that. It would be a great place to work in a reference to “Theodoric of York: Medieval Barber.”

But Brad Spellberg, an infectious disease expert at UCLA, might find the reference more accurate than we’d like.

As he told the New York Times in 2010, “For these infections, we’re back to dancing around a bubbling cauldron while rubbing two chicken bones together.”

Simply put, if research and innovation doesn’t soon start matching pace with bacterial adaptation, then modern hospitals will have to start clearing space for a few retro-styled downgrades: Like a new tuberculosis ward, lined with long rows of beds filled with people waiting to die.

The biggest causes of death back in good old, pre-antibiotic days were infections like pneumonia and tuberculosis. A small cut on the finger while trimming the rose bushes could lead to a funeral. Good times, good times.

Today, we in the developed world worry more about cancer and heart disease partly because antibiotics allow us to live long enough for those diseases to become problems in the first place. Without antibiotics, aggressive chemotherapy treatments would be nearly impossible. An appendectomy again becomes a procedure with grave risk. And you can forget about organ transplants and joint replacements.

Maybe “rubbing two chicken bones together” is going a bit overboard, but in a world without effective antibiotics, one of the best treatments could be a pungent yet strangely delicious poultice of mashed garlic and fresh honey.

So what’s the problem?

In a 2012 paper, Spellman outlined core causes for the shriveling antibiotic pipeline. Discovering new antibiotics is increasingly more difficult, expensive and time-consuming, which probably shouldn’t be a huge problem.

But antibiotics are different.

They are, in a word, amazing. They actually cure stuff. And by “stuff” we mean scary, kill-you-in-your-sleep stuff.

Take a relatively cheap, $100-bottle of pills for a week or two and a potentially deadly infection goes away.

Many other medications work differently. They manage chronic conditions that can cost tens of thousands, sometimes for the rest of a patient’s life. Think of diabetes or blood pressure medications.

Even when a new antibiotic hits the shelves, physicians are reluctant to use it without first prescribing older medications. New antibiotics become weapons of last resort in a sense, used only when nothing else works. There’s a practicality problem there.

Pharmaceutical firms look at investing more than $1 billion over a dozen years of a difficult and arcane regulatory process, only to watch their product placed in a locked case labeled “break glass in case of emergency.”

You can argue all you want about big pharma profit margins, and what they can or can’t afford to do. I don’t care who you are—$1.5 billion is big boy money, and 12 years is a long swallow on something that isn’t likely to turn a profit.

One estimate in Forbes, factoring for the price of failure, says the true cost of bringing a new drug to market is more like $4 billion to $11 billion. That’s enough to buy not just an island, but an entire island chain. And there might be enough spare change left over to hollow out a dead volcano for a modest evil lair.

One estimate in Forbes, factoring for the price of failure, says the true cost of bringing a new drug to market is more like $4 billion to $11 billion. That’s enough to buy not just an island, but an entire island chain. And there might be enough spare change left over to hollow out a dead volcano for a modest evil lair.

It’s not surprising then that just four of the world’s 12 biggest pharmaceutical companies still research new antibiotics, according to a 2012 story in The Washington Post.

And that might soon drop to three. AstraZeneca, which drops a gob-smacking $11.7 billion for each new drug developed, announced in March that they plan to reduce spending on anti-infectives.

Several ideas exist on how to replenish the pipeline. They range from changing the price structure of antibiotics to amending the regulatory process, which Congress has already addressed in some small measure with the GAIN Act.

It would be nice if those ideas offered some small portion of comfort, but what seems more likely is we need something different—Some new approach, found in some small, underfunded lab.

Not unlike Alexander Fleming and his unkempt London facility in 1928, someone will have to find a whole new way to fight infections.

Hopefully soon.

Fleming’s penicillin needed about 15 years of additional work to arrive at the bedside, and we don’t have the specter of a world war as added motivation.

[…] experts in Copenhagen last May that the rise of antibiotic resistant bacteria could mean “an end to modern medicine as we know […]