Originally appeared in the Feb. 2014 edition of Prairie Fire

By Daniel R. Anderson, M.D., PhD, University of Nebraska Medical Center

When I talk to my patients about their heart disease, we’re really talking about inflammation.

Research has well-established in recent decades the role inflammation plays in the development of plaques in the arteries or atherosclerotic disease. Inflammation is the steady drumbeat of a slow march toward heart disease that may not present any problems or even symptoms until a life-threatening heart attack or debilitating stroke.

Unfortunately, I don’t meet many of my patients until after one of those major events, and I’m confident every other cardiologist in the world can say the same thing.

Heart disease is called the silent killer for a good reason, and much of cardiology today is about managing symptoms and mitigating risk factors. By the time a cardiologist or physician is brought into the equation, much of the damage has already been done.

If we look at heart disease as links in a chain—with a heart attack or stroke as the final link—then inflammation is one of the first links.

Eliminate inflammation, and we end heart disease, right?

Probably not, even if that was remotely possible.

But we could definitely knock it off its perch as the world’s top killer. We might be able to help those people living with the silent killer and don’t even know it—like the 52-year-old who has all the outward appearances of health and vitality, but then suddenly drops dead without warning or symptoms.

The first links in the chain are the numerous injuries that cause inflammation, which in turn plays a critical role in the build-up of plaques in our arteries.

In fact, all three stages of plaque development—initiation, growth and rupture with stroke or heart attack as a final event—could be a result of inflammation from injured arteries. Injuries that promote atherosclerosis include smoking, high blood pressure, diabetes, and high LDL or “bad” cholesterol.

These risk factors cause a number of responses that result in the production of molecules and mediators that cause inflammation in the artery walls. Meanwhile, in the course of a lifetime, the smooth muscle cells and immune cells within the artery walls take up cholesterol and other proteins in the blood.

That uptake is believed to be a key player in the buildup of the fatty streak in our arteries while we are still very young—perhaps as early as our teens or even younger.

As the insults and injuries pile up in our lifetimes, immune cells are attracted to the growing atherosclerotic plaque in our arteries. One particular bad player is the “bad” cholesterol, which is the prime suspect in the death of smooth muscle cells and the breakdown in tissue that holds arteries together.

As the plaque builds up and artery walls weaken, a rupture is nearly inevitable. The rupture exposes the plaque contents to our blood’s clotting cells, which in turn attach to the plaque resulting in a thrombus that blocks blood flow. This is the heart attack we all fear.

The ultimate result can be a fatal heart attack while you’re blowing out the candles on your 52nd birthday cake. For others, it might happen at 62 or 72 or 82.

All of this is just part of being human. It was true 10,000 years ago, is true today, and will probably continue to be true for generations to come.

That inevitability, however, doesn’t mean we should all just give in and take up smoking or join the bacon-of-the-month club.

Life is full of risks. Knowing these risks—and taking the right precautions—is part of why we live more than twice as long as Americans did just 100 years ago.

Simple blood test may determine future heart risk in artery disease

While searching for evidence that might add insight into inflammatory conditions such as alcoholic liver disease and arthritis, researchers at the University of Nebraska Medical Center and the Omaha VA Medical Center made a remarkable discovery.

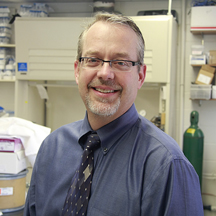

Dr. Geoffrey Thiele, a professor of internal medicine, and Michael Duryee, a research coordinator for the Division Rheumatology and Immunology at UNMC’s College of Medicine, examined a natural molecule known as MAA or malondialdehyde–acetaldehyde. MAA builds up in a person’s blood as a result of inflammation, and as the research team discovered, it also indicates the presence of coronary artery disease.

Thiele and Duryee—along with cardiologist and researcher Daniel Anderson, M.D., PhD—tested blood samples from hundreds of volunteers in two separate pilot studies. Both studies found a clear correlation between MAA and coronary artery disease, which often leads to heart disease, the world’s leading killer.The team is currently developing the discovery into an inexpensive and simple blood test that could more accurately predict a person’s risk of cardiac events like heart attack or stroke.

If successful, the test could better arm physicians worldwide with years, if not decades, of advance warning against a patient’s risk of heart attack, enabling earlier and more effective preventative care.

We now understand that not only is inflammation a central aspect of plaque and coronary artery disease, but the type of inflammation plays a critical role in how heart disease progresses. Even better, the type of inflammation might tell us what type of cardiac event might occur in the future.

So, a cardiovascular event such as suffering a heart attack and dying at 52-years-old; or chest pain at age 65, which requires artery bypass surgery; or a stroke at age 75 may depend on the specific type of inflammation which likely has been present for decades.

Yes, decades.

Several sobering studies show that 70 percent of 30-year-olds already have plaques and atherosclerotic disease.

Predicting if and how this atherosclerotic disease progresses as we age is the challenge. Right now, we are not very good at predicting who will “drop dead from a heart attack” at the age of 52 or who will live with atherosclerotic disease into old age with or without problems.

There are a number of ways to measure inflammation, however.

Several blood tests determine if you have a risk for a cardiovascular event by measuring blood levels of inflammatory molecules, including the high sensitivity C-reactive protein test, or hs-CRP for short. One of the most widely available tests, hs-CRP determines if you have an elevated risk of a cardiovascular event.

But there’s nothing out there that can accurately gauge the risk for a 30- or 40-year-old long before any of the trouble arises. Recognition of the problem at the time of a heart attack is a really a failure of medicine.

If 70 percent of adults have atherosclerotic disease by the third decade, we need to be talking about how to prevent the death at age 52. We are good at predicting risk in young adults, and we’re getting better at it. However, we miss almost 20 percent of adults who have disease because every test tells us all is well. Then the event or heart attack occurs.

Why are we missing these people?

The answer is unclear, but it may be in part due to inflammation. Until we better understand inflammation, we can’t effectively predict events in some individuals, regardless of their age.

Sadly, most cardiac patients don’t even know they have a problem until they’re recovering from a heart attack or stroke. Most troubling are those who have the first event that turns out to be fatal.

Working with Geoffrey M. Thiele, PhD, and Michael J. Duryee, M.S., at UNMC, we have found a new biomarker for inflammation, and we’re optimistic about its ability to accurately predict cardiac events. But we still have years of work before that test becomes a reality.

In the meantime, we all should be wise about our risks for a cardiovascular event:

- Treat high blood pressure and high cholesterol

- Never smoke

- Treat diabetes with weight loss and, if necessary, medications

- Follow an exercise regimen

- Eat a healthy diet

As always, the goal for all this is to avoid the worst-case scenario: “Dead at 52.”

We also know that inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis result in systemic inflammation, and local infections like gingivitis, prostatitis, bronchitis, urinary tract infections and gastric inflammation are associated with plaque formation and atherosclerosis. These inflammatory diseases also accelerate plaque development, atherosclerotic disease and cause cardiovascular events earlier in life.

Being aware and treating these issues will serve you well.

The risk is real. You know what to do.

Treat your known medical problems.

Don’t smoke, lose the weight, eat right and exercise.

If you do all these things, your inflammation will decrease, and your risk of a cardiovascular event will also decrease or be delayed by years.

Hopefully you don’t have an event until you are 62 or 72 or better yet, not at all. That is unquestionably a real possibility, with aggressive treatment.

———

Daniel R. Anderson is a practicing cardiologist and basic science researcher at the University of Nebraska Medical Center. Anderson received his medical degree from UNMC, and completed his doctorate in molecular and cellular immunopathology at UNMC. When he’s not treating patients, Anderson works with colleagues Geoff Thiele, PhD, and Michael Duryee on developing a better diagnostic test for cardiovascular inflammatory diseases.

UNeMed Corporation is the technology transfer office (TTO) for the University of Nebraska Medical Center. UNeMed serves researchers, faculty and staff who develop new biomedical technology and inventions, and strives to help bring those innovations to the marketplace for a healthier and better world.