by Bill Hadley, UNeMed | Oct. 3, 2012

When a word or symbol is of a character to be appropriated, as a trademark, it becomes property which a competitor has no right to use, either alone or in connection with matter to which its owner lays no claim, without such owner’s consent.

You get up in the morning and grab a cup of coffee on the way to work. You know what to expect just by looking at the well-known Starbucks siren logo on the cup. You arrive at work, turn on your computer and hear the all-too familiar chime of a Microsoft Windows PC booting up.

For lunch, you stop off at a fast-food restaurant and know that they’re handing you your favorite sandwich at McDonald’s because the Golden Arches haven’t changed much since you first started going there. On your way back home from work, you stop by a shoe store to buy some Nikes. You easily locate a pair by the ‘swoosh’ on its side.

All these product features – the logo, the chime, and the packaging – are trademarks. Trademarks are distinctive signs or indicators used by a provider of a good to identify the provider and distinguish it from its competitors. Thus, a good trademark provides for quick and easy product recognition by consumers.

Trademark law exists only to protect the underlying mark, not the product the mark represents. Thus, trademarks cannot be used to protect an invention (Patents) or literary works, software, or music (Copyrights). Nevertheless, trademarks are an integral part of intellectual property protection.

Today, we’d like to take a few minutes to explain how trademarks work, how they don’t, and how they differ from more well-known protection mechanisms.

What exactly is a Trademark?

The Apple brand includes the iPhone, iPad, and iPod

Simply put, trademarks are (nearly) anything that can be used to identify the creator of a good. Because we often attribute the quality of a good to its producer, trademarks are, ipso facto, also signifiers of consumer good will and reputation. By way of illustration, consider: one of the reasons the iPad has been so successful is that, through production of other quality portable electronics such as the iPod and iPhone, consumers attributed the Apple brand with production of quality electronics. Branding electronics with the distinctive Apple logo, therefore, lends an aura of quality – of value – that the product might otherwise lack (at least initially).

The ultimate goal of trademark law is to prevent commercial confusion. Trademarks protect the goodwill of a consumer toward a company (and its reputation) by providing the company a monopoly on the use of the mark attached to its products. Additionally, trademarks protect consumers: if Apple wasn’t able to exclude other electronics manufacturers – say… Samsung – from placing the apple icon on Samsung electronics, consumers might mistakenly purchase a Samsung electronic device believing it to have the quality of an Apple product. (Please note that this comparison is only for illustrative purposes only – the author has no actual opinion on the value of Samsung and Apple products. He still proudly rocks his Blackberry!)

The Different Categories of Trademarks

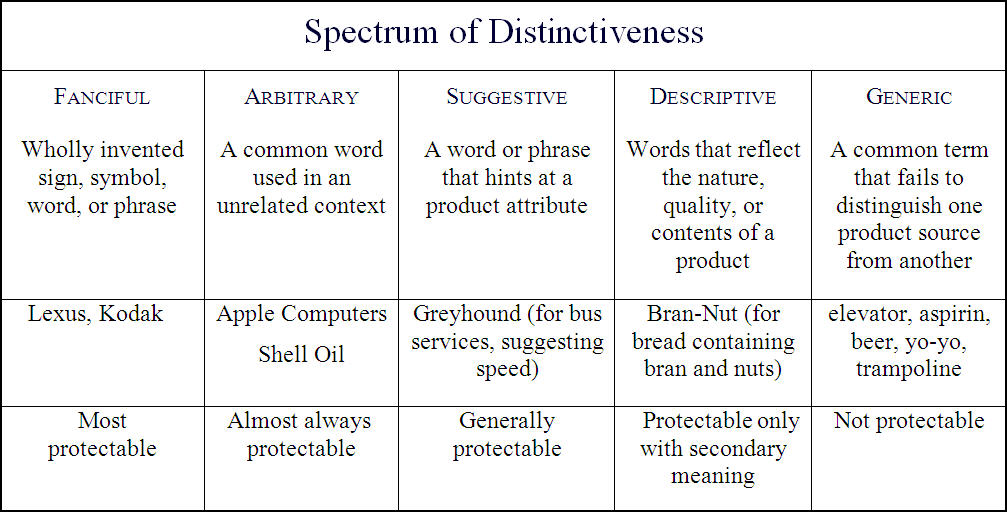

Trademarks are classified in levels of ‘distinctiveness’ – marks which are more “distinctive” (i.e. “fanciful” or “arbitrary”) are afforded more preferential treatment than trademarks that are less so (i.e. “descriptive” or “generic” marks). Trademarks are associated with a category of distinctiveness based on how the mark relates to the product it signifies: the more related the mark is to the product, the less distinct it is. For an illustration of this principle, take a look at the table below:

Table adapted from https://gbr.pepperdine.edu/tag/trademark/

Thus, we can see that the context in which the mark is used is of great importance: ‘Apple’, for example, may be a strong arbitrary trademark for a computer, but would probably be a much weaker descriptive or generic mark for an orchard.

Trademark Limitations

While many types of identifying marks are available for trademark protection, there are a few important limitations. For example, trademarks cannot be “functional” – that is, they cannot perform an action or otherwise contribute to the effectiveness of the product they represent. Thus, the classic contour shape of a Coca-Cola bottle is trademarkable (as it does not contribute to the pleasure derived from drinking a coke), whereas the “wide-mouth” shape of a soft drink can might not be able to be trademarked, because the wider mouth itself contributes to ease of pouring the drink – and thus utility is derived from the design.

Another type of limitation is the ‘Genericization of a Mark’. It is possible for a once arbitrary or fanciful mark to, over time, become generic due to over-saturation of its use. For example, ‘Aspirin’ used to be a trademarked name of acetylsalicylic acid owned by Bayer, but due to its colloquial use for “painkiller”, it has been deemed a generic mark in the US. That is to say, today, if someone wants an ‘Aspirin’, it does not necessarily mean that they want “acetylsalicylic acid produced by Bayer”, it simply means that they want to take a painkiller. Thus, the term ‘Aspirin’ does not serve to identify the producer of a good any longer and thus ceases to be a trademark. Other famous genericized marks include Kleenex for tissues, Xerox for paper copies, Scotch Tape for clear adhesives strips, and maybe even ‘Google’ for internet searches. Understandably, large companies invest substantial resources in policing the use of their marks in hopes of preventing “genericide”.

Trademark Registration

Common law trademark rights may be obtained automatically from use of a mark, alone, in commerce. Alternatively, a mark may also be registered – so long as there is no identical active mark currently in use – at the USPTO. Actual use in commerce is not required for a registered mark; instead, a bona fide intent to use the mark in commerce is sufficient.

Without registration, a mark protected by common law is only valid in the region in which the marked goods are actually sold. Registration of a trademark ensures that the mark is valid and can be used nationwide. Runza, for example, has a trademark registered at the USPTO and, therefore, the Runza trademark has effect nationwide. If the mark were not registered, however, it may not be enforceable in states like Colorado, where no Runza franchises are in business.

After a trademark is registered, a company may use the well-known circle R (®) icon with its mark. Marks that are pending registration or are asserting common law rights may use the TM symbol (™). Using the ® icon on a mark that is not registered is illegal.

Why You Should Learn About Trademarks

UNMC Discover is a registered trademark owned by Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska.

As a UNMC employee, trademarks will likely only very rarely be of importance to you (UNMC and its employees/students are generally not involved in selling a product or good). Nevertheless, in some cases a familiarity with trademark law might be important. For instance, if you were to spin-out a start-up company around a piece of intellectual property developed here at UNMC, you may want to develop a mark to identify the goods that company intends to sell.

Additionally, you may be involved with work involving the use of other entity’s marks, such as UNMC’s mark, or marks of collaborating institutions or industrial partners. In these circumstances, it is important to be able to recognize their marks and to know when and how that mark may be used.

If you are interested, the University of Nebraska policy on trademarks is set forth in Executive Memorandum No. 20, which states:

(T)he Vice President for Business and Finance and the Principal Business Officer on each of the campus of the University, with the written approval of the Vice President and General Counsel or an attorney on his or her staff, is hereby granted the delegated authority to develop, adopt, and protect University trademarks, trade names, copyrighted designs and other indicia on behalf of the University of Nebraska, its major administrative units and the various administrative subdivisions thereof.

Trademarks related to UNMC may be disclosed to UNeMed via the following form. Supplemental information about trademark law can be found on Harvard’s Berkman Center for Internet & Society website.

If you have any questions or comments, please do not hesitate to contact the authors or leave a comment below.

Join us next week when we discuss the licensing process.

|

About the Author

|

Bill is a licensing associate at UNeMed, where he handles evaluation, development, marketing, and licensing for medical device, software, and telemedicine-based invention disclosures. He received a B.S. in Chemistry from the Colorado School of Mines and a J.D. from the Creighton University School of Law. Bill is currently in training for next fall’s intramural volleyball league, where he has personally guaranteed at least one victory for the mighty UNeMed Volley Llamas. Contact Bill: Bill.Hadley@unmc.edu |

|

About the Author

|

Dallin is a Legal Intern at UNeMed, where he works together with the Contract Specialist to protect, maintain, and enable the contractual rights of UNMC researchers in the intellectual property that they develop. He received a B.S. in Chemical Engineering from the University of Utah and is a student at Creighton University School of Law. Dallin enjoys spending time with his wife and daughter, going on walks, watching movies, reading books together with his family, and playing trivia games. He also likes to play sports, especially basketball. Contact Dallin: Dallin.Call@unmc.edu |