by Joe Runge, UNeMed | May 8, 2014

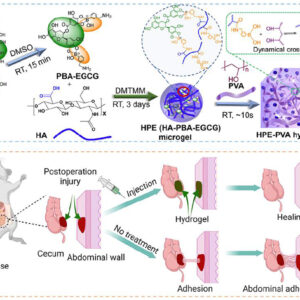

Babies born with congenital heart defects rarely survived childhood. Today, 85 percent of babies born with congenital heart defects survive to adulthood. That happened because surgeons learned how to reconstruct a baby’s heart through a series of unimaginably complex surgical procedures.

How those surgical procedures came to be is more complex than the surgery itself. The miracles produced in a few hundred years of modern science embolden audacious questions:

- Can we reprogram a patient’s cells to attack his tumor?

- Can we assess an individual patient’s risk for disease by looking at her DNA?

- Can we reconstruct a baby’s defective heart?

What emboldens the question is the possibility of answer. The currency of innovation is the new and powerful ways that researchers can test their ideas but the most innovative questions are the most challenging to test. If no one has ever thought to ask the question then there is likely no known way to test it.

Medical researchers not only invent a new way to treat a disease but also a new a way to find out if it works. Before you can innovate, you have to innovate.

For example, a team from Johns Hopkins invented one of the first procedures to alleviate congenital heart defects in the 1940’s. The procedure bypasses the baby’s beating heart by cutting major arteries and reconnecting them to major veins.

To learn how to do the procedure, the team invented a way to surgically create congenital heart defects in dogs. Then they invented a way to surgically relieve the defect. It took years and hundreds of failures.

The first dog in which the team successfully created and then treated the defect was named Anna. Her portrait hangs at library at Johns Hopkins—an honor usually reserved for the human faculty.

The currency of innovation is the impossibly elusive data needed to actually answer the question. To reconstruct the baby’s heart first you must reconstruct a dog’s heart. To reconstruct the dog’s heart, you must first create an accurate model of the baby’s defect that you seek to correct.

To even ask the audacious question you need access to the problem, expert knowledge to understand it, and a creative approach to treat it. To answer your question you need the tools to test your idea. The more audacious the question, the more innovation is needed to bring about the answer.

That answer may require a genetically modified mouse that is susceptible to human tumors; it may be a national database of DNA sequences from thousands of patients with a disease; or it may be a little dog named Anna, and her improbable creation.

[…] Original post: Innovate to Innovate: A new breed of dog needed for blue babies … […]

[…] biomedical research, it sometimes requires that researchers essentially invent a new animal, like Anna, an adorably scruffy mutt famously engineered by researchers at Johns Hopkins in pursuit […]