by Charles Litton, UNeMed | October 25, 2017

Darkness often represents uncertainty. The unanswered question. The unsolved problem.

Darkness often represents uncertainty. The unanswered question. The unsolved problem.

Illumination, then, reveals the unknown. Lights the path to answers. Unveils potential solutions.

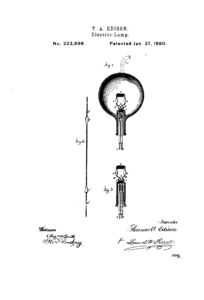

It should be obvious why the light bulb has become one of the more persistent clichés on the planet. The symbolic meaning of a light bulb has entrenched itself in the public psyche as the ultimate brand for inventive creativity. It’s true that the light bulb is a cornerstone achievement for modern civilization, but that doesn’t fully explain its symbolic ubiquity.

It’s really about the light itself: the antidote for darkness.

Before Thomas Edison, the symbol was a simple flame, such as you might see flickering from a candle or oil lamp.

But look closer at Edison’s light bulb.

He tried hundreds, if not thousands, of different concepts in his quest for electric light—Different filaments, in different shapes, in different sizes and different metals, encased in different gases… The original idea turned out to be something different than what ultimately succeeded. And this was long, long after people devised flaming sticks, candles, oil lamps, gas lanterns and whatever else they used in times past to light the way.

And the journey continues today: That first light bulb looks considerably different than today’s modern LED light. What new forms—presently inconceivable—will light the darkness for us in another 100 years?

And the journey continues today: That first light bulb looks considerably different than today’s modern LED light. What new forms—presently inconceivable—will light the darkness for us in another 100 years?

That mystery of an invention’s maturation is the very core of innovation. It’s the incremental change from the first grand idea to the thing that emerges from the development process…and then continues to evolve.

As a commercialization and technology transfer office for a major university medical school, UNeMed sees first-hand how innovations can play out like this.

Sometimes the idea is too advanced to work in the here and now.

We saw that about 10 years ago when an inventor proposed to solve the third-world’s lack of surgical access. His idea was essentially a laparoscopic tool with a camcorder stuck to the top. (Think of the ill-fated Flip Camera, which was THE go-go gadget for about 20 minutes in 2009.)

The laparoscopic invention was probably unworkable and impractical only because the idea was too advanced for the time.

Then smartphones and the iPad happened.

Now the portable laparoscope is not only entirely possible and actually feasible, it is also, dare we say, likely.

Portable Laparoscope inventor Chandrakanth Are, M.D., (right) chats with Rich Abraham of Vention Medical during a recent partnering event hosted by UNeMed earlier this year.

It might actually bring minimally invasive surgery to places where such lavish, first-world luxuries were but a dream only five years ago.

Even as the portable laparoscope relied on external technologies, most of the innovations UNeMed sees will need to run grueling marathons.

One marathon began as an unnamed discovery back in 1993. (Founded in 1991, UNeMed still had that new tech transfer office smell.)

Years later, we came to know the discovery as a synthetic peptide called EP67, and marveled at its ability to stimulate the human immune response to any number of things. Primarily, it showed promise as a way to produce vaccines for everything from the common flu to even chemical dependency.

Later, it proved to be a potent immune stimulant all by itself. The technology continued to grow and evolve as the inventor, Sam Sanderson, PhD, continued tinkering with different formulations.

Different approaches.

Different applications.

Sound familiar?

A startup company, Prommune was born from the work in the early 2000s.

A nanoformulation of the technology followed.

Then a handful of analog formulations.

And most recently, a little more than a year ago, Sanderson and Prommune were awarded about $4 million in federal grants to examine EP67’s use against dangerous infections, including methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus, or MRSA.

What began in 1993 was little more than an intriguing discovery with a lot of promise and hope. Just as Edison’s light bulb bears little resemblance to modern light fixtures, so too does Dr. Sanderson’s EP67 from his first discovery 25 years ago.

A lot of blood, sweat, and too many tears have passed under the bridge since then. The inventor, Dr. Sanderson, unexpectedly passed away in August.

But Prommune and EP67—and the portable laparoscope and heaps of others—live on.

And so continues the hard work of lighting the way to better health.

Late UNMC researcher Sam Sanderson, PhD, seen here during a quality control test in his Omaha lab in 2015.