Greg Gordon, MD, founded Radux Devices around two inventions he created—including the Steradian Shield, above—that help protect physicians during fluoroscopic procedures.

by Charlie Litton, UNeMed | August 11, 2020

The type of innovative technologies blossoming at Nebraska startup company Radux Devices brings to mind, paradoxically, a 100-year-old Vaudeville routine.

Patient: “Doctor, it hurts when I do this.”

Doctor: “Then don’t do that.”

The humor there is perhaps best described as the measure of empathetic annoyance at such “medical” advice. The advice isn’t necessarily bad, it just doesn’t do much to solve to core issue of pain.

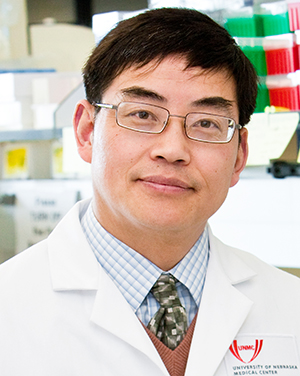

How a century-old comedy act dovetails with cutting technology speaks to the very nature of innovation. In this case, Greg Gordon, MD, an interventional radiologist, suffered pain every time he did his job.

Inventor/Founder Greg Gordon, M.D., presents his startup company, Radux Devices, during UNeMed’s 2017 Industry Partnering Summit.

He couldn’t very well stop doing his job, as an old Vaudevillian might have him do. Discomfort, chronic pain, debilitating back injuries and even dangerous radiation exposure are all part and parcel to an interventional radiologist’s existence.

But here’s the thing: It didn’t have to be. Dr. Gordon just found a different, better way to “do that” so it wouldn’t hurt anymore. He solved the core problem.

And now he has a revenue-generating company built around those ideas.

That’s all innovation is.

Not all innovations are as potentially transformative as Dr. Gordon’s devices, but they all seem to share that same DNA.

The problem

Interventional radiology or fluoroscopic procedures actively use x-rays to help guide physicians as they place things like catheters and stents. Using x-rays are also helpful to monitor blood flow and find blocked arteries in real time.

The trouble with fluoroscopic procedures is two-fold.

First, they’re flooded with—surprise—x-ray radiation. That is not a big problem for most patients. They might see that level of radiation only a few times in their entire lives.

The physician, however, might perform several of those procedures in a single day. All that radiation adds up, so physicians must take great care to limit their exposure.

The interventional radiologists who perform these procedures wear heavy, lead-lined protective garments, which lead to the second part of the problem: musculoskeletal injuries.

While wearing a 15- to 30-pound apron, the physicians often try limiting their exposure by standing in ways that keeps them as far removed from the x-ray field as possible. That usually means leaning in odd and uncomfortable angles. It means using less-than-preferred techniques just to avoid feeling the stabbing pains and dull aches that seem to grow more intense with each passing day.

The Standard of Care

The standard of care in cardiac fluoroscopic procedures is to access the patient’s aorta through in the radial artery in the arm. The left is the easier route because the artery on that side has one less curve to navigate. However, using the left radial artery is often awkward and uncomfortable because most surgeons are right-handed. A right-handed doctor using left arm access usually requires leaning into the radiation field, over the patient, who themselves are often positioned in awkward and uncomfortable positions.

Many physicians in cardiac fluoroscopic procedures can easily avoid the discomfort—and its potential for long-term injury—in favor of using the right arm or the femoral artery in a leg.

The problem with the right arm is one of human anatomy. The right side has that extra curve, which is even more complicated with shorter or older patients. The arteries in shorter people make tighter curves, and older, more fragile patients often have arteries that are more delicate. A physician might struggle for half-an-hour to finesse a catheter into position from the right arm. The same procedure on the same patient might take only five minutes when performed from the groin.

Femoral access may be no more complicated than from the left radial artery, but going through the groin is well documented for carrying a significantly higher risk of complications and failures.

Don’t do that, do this

In 2012, Dr. Gordon solved the problems with two seemingly simple ideas.

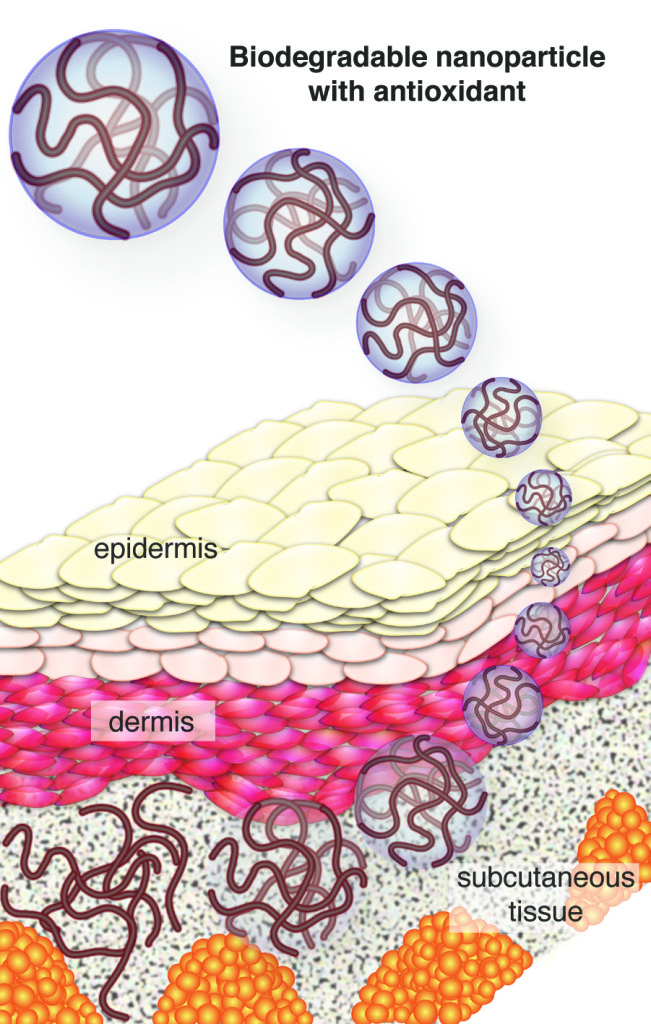

One is called the “Steradian Shield,” which is about the size of a steno notebook. It’s a sterile, moveable device that can be placed virtually anywhere, in any position, to block the radiation gaps from entering the physician’s workspace.

Another device, called “StandTall,” helps physicians better manage and direct the catheters used during fluoroscopic procedures. StandTall was designed to help bring the workflow closer to the surgeons while at the same time moving them further away from the radiation.

StandTall is a device Greg Gordon, M.D., invented and is among the products he sells through his startup company, Radux Device.

Such simple improvements may seem inconsequential, but the change is dramatic in a fluoroscopic suite. What they’ve essentially done is eliminate all the troubles associated with left-arm access, allowing physicians to comfortably perform left radial procedures from the right table set up, giving that gold standard of care a chance for wider use in the United States. The benefits just cascade from there.

No longer in pain and in fear of radiation exposure, physicians can perform procedures faster, more efficiently and more of them. Their use of the preferred access sites leads to better patient outcomes, less complications, and lower costs. A radial access procedure, on average, costs $1,000 less than a femoral access procedure.

Meanwhile the hospital and catheter labs increase the number of procedures that can be performed in a day, with fewer complications and far fewer expenses.

If there are any losers, it might be the chiropractors and orthopedic specialists that interventional radiologists seek out for relief.

Word from the field

In an interview published in the March issue of Cath Lab Digest, one physician found that using the StandTall Device helped him improve his radial access rate, going from 80 percent to 95 percent.

“The StandTall has allowed me to adopt a left radial first approach for bypass cases, because I can use a left radial access without having to lean over the table,” said Ryan D. Madder, MD, Section Chief of Interventional Cardiology and Director of the Cath Lab at the Frederik Meijer Heart & Vascular Institute at Spectrum Health in Grand Rapids, Michigan.

He added: “…we have seen an increase in radial access rates as a whole for our entire lab and along with that, we have seen a reduction in our access site bleeding complications. I do think the StandTall has made it more comfortable for operators to use left radial access in bypass cases.”

For the dry prose of a practicing clinician, that’s a ringing endorsement. It’s made all the more remarkable with the knowledge of how fraught and treacherous the road for a startup can be.

At Radux, the first few years was a constant struggle to secure funding just to build a few prototypes.

As it turned out that was the easy part.

The long road

Inventor Greg Gordon, MD, checks the alignment on an early prototype of his Steradian Shield invention during a proof of concept study in 2015. The study found that the shield blocked significant levels of radiation during fluoroscopic procedures.

The University of Nebraska provided some help with a proof of concept grant, and the state’s burgeoning venture capital community stepped in as well.

But one thing many people don’t know about innovation is that the first prototype is just that: The first.

What follows are countless iterations, and follow-on experiments to test incremental changes and improvements. All the while, the fund-raising beast is voracious and must be fed, constantly.

By 2016 Dr. Gordon stepped back from full-time practice in order to help his startup grow.

The extra time appeared to pay off.

Radux secured FDA registration, and finally rolled out its official launch with a national distributor in September 2019. There was actually revenue, which is no small feat for a fledgling startup.

Even better, more and more hospitals were buying into the devices Radux created: It was an easy sell once doctors and administrators were able to use them.

What pandemic?

Today, in spite of a pandemic that shut down all non-emergency procedures, Radux has continued its momentum. So far, Radux boasts nine full-time employees, and their devices are in more than 70 hospitals nationwide and a high reorder rate, supporting their sales model and product acceptance.

And when face-to-face meetings become a thing again, those numbers are expected to keep growing.

It would be shocking if it didn’t.

The undeniable thing about these devices is that when they get into the hands of health care professionals, the response has been overwhelmingly positive.

In essence, they tell Radux it hurts to do what they do.

Radux gives them far more than an old punchline.

Read article