OMAHA, Neb. and STAMFORD, Conn. (Aug. 31, 2016)—The University of Nebraska Medical Center and Purdue Pharma L.P., have entered into a partnership to advance graduate education and scientific research that could lead to new drug therapies for patients.

The partnership will kick off on August 31 with UNMC and Purdue Pharma leaders attending a scientific symposium at UNMC from 8 a.m. to noon in the Michael F. Sorrell Center for Health Science Education on campus. UNMC researchers studying neurosciences will talk about their research. As part of this long-term partnership, these symposia will be repeated several times annually, each one with a different scientific theme, and each time creating opportunities for scientific exchanges and personal interactions between the organizations.

The alliance will promote, develop and expand research and educational exchange in the neurosciences related to pain, the central nervous system, and other chronic diseases. One of the goals is to close the gap between academic research and drug development by shortening the lengthy path of drug development from idea to potential commercialization through workforce development and education, as well as research.

“Collaborations between industry and academia are important to drive innovation for patients suffering from pain and other chronic diseases,” said Alan W. Dunton, M.D., Senior Vice President and head of Research & Development, Purdue Pharma. “Our R&D team is continually working to understand the pathophysiology of these diseases so that we can identify new ways to develop and investigate potential therapies. Working with an institution with the research experience and capabilities of UNMC will enhance our ability to accomplish this important goal.”

UNMC and Purdue Pharma will have opportunities to work together on research that may lead to new product development.

“We are pleased to partner with Purdue Pharma. The alliance will aid in advancement of UNMC’s mission to conduct basic and clinical research toward the goal of improving the lives of patients,” said Jeffrey P. Gold, M.D., UNMC chancellor. “Pharmaceutical companies are looking more toward academic medical centers like ours for the talented graduate students and researchers who will develop the next generation of potential therapies and products.”

Jennifer Larsen, M.D., UNMC vice chancellor for research, said the partnership signifies a commitment to identify strategies for understanding pain and developing new approaches or therapies for pain that avoid substance abuse as well as other types of neuroscience research.

“More of our investigators are interested in taking their discoveries all the way to commercialization,” said Dr. Larsen, Louise and Morton Degen Professor of Internal Medicine. “Having a partnership with investigators in the industry is another way of increasing UNMC’s capacity and to accelerate intellectual property to commercialization.”

“UNMC has deep expertise and broad areas of research, internationally recognized faculty, and significant overlap with our strategic interests in the treatment of pain, central nervous system diseases, drug delivery and formulations,” said Don Kyle, PhD, Vice President of discovery research, Purdue Pharma. “We are building a new model for industry-academic relationships with this partnership that will enable open and frequent dialog across disciplines and between the two organizations. This model will not only drive innovations in R&D, but will also facilitate learning and create professional growth opportunities.”

The partnership also includes a new Purdue Pharma Scholar program with funding for graduate students conducting research in neuroscience, particularly pain research. Three first- or second-year graduate students per year will receive a one-year graduate tuition scholarship. During the year Purdue research leaders will visit with students and students will have the opportunity to visit Purdue where they will have access to research facilities. Students will present their research at an annual Purdue Pharma Neuroscience Research Conference at UNMC.

Dele Davies, M.D., UNMC vice chancellor for academic affairs and dean for graduate studies said UNMC is encouraged by the opportunities the partnership offers for graduate students and faculty.

“Purdue Pharma’s support of UNMC graduate students through scholarships in particular will spur new research interests in pharmaceutical and neurosciences related to pain management and control,” Dr. Davies said. “The partnership blends UNMC’s extensive and growing expertise and training programs in many health disciplines with Purdue Pharma’s strong track record of drug discovery, formulation and development.”

About Purdue Pharma L.P.

Purdue Pharma is a privately-held pharmaceutical company and is part of a global network of independent associated companies that is known for pioneering research in chronic pain and opioids with abuse deterrent properties. The company’s leadership and employees are committed to serving healthcare professionals, patients and caregivers quality products and educational resources to support their proper use. Purdue Pharma is engaged in the research, development, production and distribution of both prescription and over-the-counter medicines and hospital products. With Purdue Pharma’s expertise in drug development, commercialization, and life-cycle management, the company is diversifying in high-need areas to expand through strategic acquisitions and creative partnerships. For more information please visit www.purduepharma.com or follow the company on Twitter, Instagram and LinkedIn.

In a pair of reports prepared for the House Judiciary committee, the Government Accountability Office looked for solutions to a few problems with U.S. intellectual property law. The end result was a mixed bag of proposals that varied between the elegant and the bizarre.

In a pair of reports prepared for the House Judiciary committee, the Government Accountability Office looked for solutions to a few problems with U.S. intellectual property law. The end result was a mixed bag of proposals that varied between the elegant and the bizarre.

An invention begins with an idea. For example, say a researcher is studying the effects of second-hand smoke on the lungs of ferrets. The researcher needs a certain material to conduct the study. As a legal intern, I helped to draft and negotiate a

An invention begins with an idea. For example, say a researcher is studying the effects of second-hand smoke on the lungs of ferrets. The researcher needs a certain material to conduct the study. As a legal intern, I helped to draft and negotiate a  OMAHA, Neb. (June 6, 2016)—UNeMed expanded its approach to commercializing its portfolio of inventions and innovations, announcing today a deeper relationship with Straight Shot, an Omaha accelerator focused on helping technology startups.

OMAHA, Neb. (June 6, 2016)—UNeMed expanded its approach to commercializing its portfolio of inventions and innovations, announcing today a deeper relationship with Straight Shot, an Omaha accelerator focused on helping technology startups.

OMAHA, Neb. (May 17, 2016)—There is $2.5 billion in federal grant money available through the SBIR/STTR program, and an upcoming “road show” will help researchers, innovators and entrepreneurs learn how they might make use of the funding opportunities.

OMAHA, Neb. (May 17, 2016)—There is $2.5 billion in federal grant money available through the SBIR/STTR program, and an upcoming “road show” will help researchers, innovators and entrepreneurs learn how they might make use of the funding opportunities.

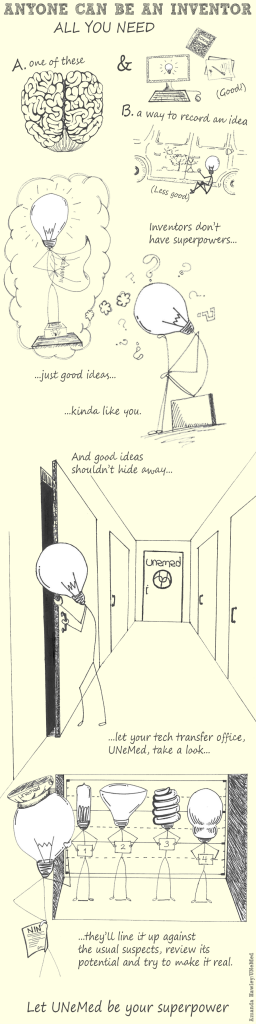

Yes. Anyone can be an inventor.

Yes. Anyone can be an inventor.