CORRECTIVE AMENDED, 7/11/13, 12:58 p.m.

by Charles Litton, UNeMed

OMAHA, Neb. (July 10, 2013)—It’s a virtual certainty that everyone over 50—more than 98 million Americans—has coronary artery disease. So do 70 percent of 40-year-olds. And about half of people in their 20s and 30s probably have it too.

Yet heart disease doesn’t kill everybody.

Understanding the difference between those who die and those who don’t has been a confounding riddle for modern medicine.

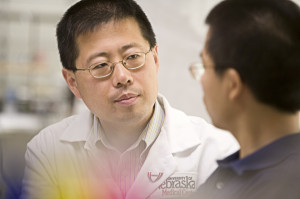

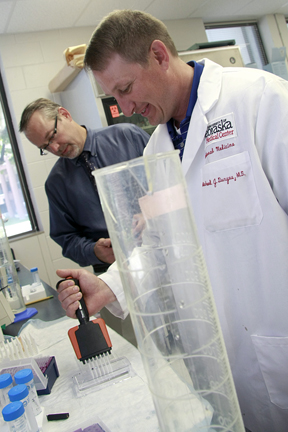

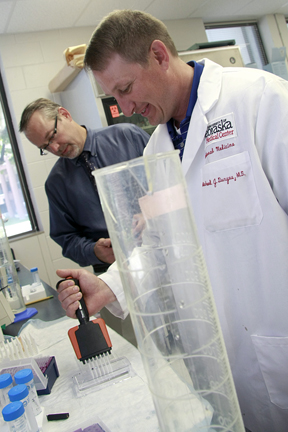

An interdisciplinary team of researchers at the University of Nebraska Medical Center in Omaha—Dan Anderson (left), Michael Duryee (right) and Geoff Thiele (not pictured)—believe they found a way to determine who will develop potentially deadly heart disease with a simple blood test.

An interdisciplinary team of researchers at the University of Nebraska Medical Center believe they’ve made a potentially ground-breaking discovery. It’s a simple test that effectively determines whether or not a patient is harboring the dangerous type of heart disease that kills one in four Americans every year. Even better, the test could tell an apparently healthy 40-year-old that they are in the earliest stages of the world’s No. 1 killer.

Most people live with it, blissfully unaware. They only develop complications late in life, such as chronic chest pain or angina. But there are others who unexpectedly suffer a debilitating or fatal heart attack. It doesn’t seem to matter if they’re young, fit and trim or a world famous actor vacationing in Europe.

Coronary artery disease is the accumulation of plaque deposits inside the arteries that feed the heart. As plaque builds up, it restricts blood flow. For people who have the unstable and usually lethal form of the disease, a piece of that plaque can break off creating two potential problems.

While that debris is swept away in the blood stream, things like blood platelets and clotting factor start building up at the rupture site, creating a bottleneck that blocks blood flow. And the debris itself can get wedged further down the line where it could also dam off blood flow.

Either way, the result is a sudden heart attack or stroke.

Unfortunately, that heart attack is too often the first indication that a patient has the lethal form of the disease. But UNMC’s new test could change that.

Dr. Geoff Thiele, a professor of internal medicine, and Michael Duryee, a research coordinator for the Division Rheumatology and Immunology at UNMC’s College of Medicine, made the initial discovery. While looking for clues to help understand inflammatory conditions such as arthritis and alcoholic liver disease, they focused on a molecule that is a strong indicator of inflammation. Known as MAA or malondialdehyde–acetaldehyde, the molecule also appeared to indicate the presence of coronary artery disease.

Dr. Geoff Thiele

“We thought it was cool scientifically, but we’re not clinical guys,” Duryee said. “We don’t see this everyday.”

Thiele and Duryee brought in cardiologist Dan Anderson, an assistant professor in the Division of Cardiology who is a rare blend of researcher and practicing physician. He has a frontline view of the battle against the world’s most prolific killer, which annually takes more than an estimated 17 million people. Heart disease accounts for 600,000 American deaths every year.

“In the current realm of understanding disease, we know that inflammation is important in cardiovascular disease,” Dr. Anderson said. “But we really don’t understand a lot about why or how.”

By current measures, Anderson said, about 30 percent of people with heart disease slip through the cracks. For those people, the first indication of trouble may be a killer heart attack in what Anderson called “a failure of medicine.”

“We should have seen and recognized this decades prior, and prevented it,” he said. “People tend to feel okay and think they’re okay. But they’re not even seeing the tip of the iceberg.”

But there are others with the disease who suffer few, if any, ill-effects. Predicting which patients will develop the more deadly form of heart disease is little more than a guess.

Then Dr. Thiele and Duryee knocked on the door.

“I said, ‘Oh, my God.’ From a clinical diagnostic perspective, this becomes invaluable to help understand those different groups of patients,” Dr. Anderson said.

Over the course of two pilot studies, the team tested hundreds of volunteer patients’ blood, and found a remarkable correlation.

“Right now, the data really is incredible,” Dr. Thiele said.

It’s no minor feat for pilot studies to generate significant results with such a small group of patients. Most other studies in cardiovascular research don’t show significant results until thousands of patients are included in a study, Dr. Anderson said.

“We’re seeing differences where we haven’t been able to predict those differences before, and I think that’s the value,” he said.

The initial results have gained attention elsewhere.

The research team and UNMC’s technology transfer office, UNeMed Corporation, are currently in preliminary discussions with several companies on how to translate the results into products that can better factor in a patient’s risk of heart attack

Thiele said that any test developed from the discovery would be cheap and easy to implement with any clinical lab facility’s existing equipment. It would be a simple blood test, not unlike tests that measure blood-sugar levels for diabetics.

The next rounds of testing will be critical to understand how accurate the test can be, particularly studies that follow individual patients over the course of five or 10 years, Duryee said.

If successful, researchers hope the test could be used to definitively tell younger patients in their 40s, 30s or even their 20s whether or not they will develop potentially fatal heart disease. Perhaps even patients in their teens could get early warnings, and begin taking preventative measures.

“That’s what we don’t know, but that’s our goal,” Dr. Anderson said.

***

CORRECTION: The sixth paragraph was amended and the seventh paragraph added to more accurately describe the effects of buildup and subsequent rupture of plaque in coronary arteries.

Read article

Gene patents have been the focus of attention on every media outlet since the

Gene patents have been the focus of attention on every media outlet since the