by Bill Hadley, UNeMed | Jan. 9, 2013

President Kennedy, his wife Jacqueline, and Texas Governor John Connally in the presidential limousine, minutes before Kennedy was assassinated on Nov. 22, 1963.

On November 22, 1963, at precisely 12:30 pm, shots rang out from the Texas School Book Depository overlooking Dealey Plaza in Dallas, Texas. The shots tore into the motorcade that traveled through the plaza, wounding Texas governor John Connally, bystander James Tague, and killing John F. Kennedy, the 35th President of the United States. Also present that day was Abraham Zapruder, a russian immigrant who had, on a whim, decided to film the motorcade as it passed through Dealey Plaza. While there were many photographers present, in a bizarre stroke of fortune (or misfortune), Zapruder was one of the few people actually capturing the procession on film – and one of the fewer still who were capturing film from a vantage point that provided an unimpeded view of the presidential motorcade as the bullets ripped through it.

All told, the “Zapruder Film” comprises 26.6 seconds (486 frames) of footage documenting the event. Recognizing the value of the footage, Zapruder promptly sold the original film to Life Magazine for $150,000 (just over $1.1 million today). Three years later, Josiah Thompson, a former employee of Life, decided to publish his own account of the tragedy in his book Six Seconds in Dallas. Unable to receive Life’s permission to use frames from the Zapruder Film in his recounting of the events, Thompson hired an artist to re-create the relevant frames from the film in the form of charcoal sketches, which were subsequently included in the book for analysis.

Shortly thereafter, Life sued Thompson for infringing its copyright in the Zapruder Film and, inherently, the still frames that make up the film. Among other defenses, Thompson claimed that his re-creation of the frames was permissible under the Fair Use Doctrine – a principle that permits copyright infringement in certain circumstances (note: at this time Fair Use was a common law principle – today it is formally codified in the Copyright Act). In 1968, the Federal District Court for the Southern District of New York heard the case and ruled in favor of Thompson (Time, Inc. v. Bernard Geis Assocs., 293 F. Supp. 130 (S.D.N.Y 1968).

If you’re scratching your head over this one, don’t feel bad. Ostensibly, this is a textbook case of copyright infringement: after all, Thompson duplicated a creative work – the Zapruder Film/frames – to which he had no legal claim, without the permission of the lawful owner, and published the duplicate images for his own financial benefit. So how on earth did the court find this permissible? To understand, it’s imperative that one is familiar with the Fair Use defense – perhaps the most ambiguous, frustrating, non-sensical, and necessary, limitation on the scope of copyright protection.

The Fair Use Defense and the Copyright Act of 1976

Fair use (also called “fair dealing” in certain foreign jurisdictions) is an affirmative defense to a charge of copyright infringement that permits limited use of a copyrighted work without permission from the copyright holder. Typical fair uses of a copyrighted work are for purposes such as criticism, commentary, scholarship, and parody. At its core, fair use is representative of the balance inherent in all intellectual property schemes; in this case, it is recognized that, in some circumstances, public policy dictates that limited use of copyrighted material should be encouraged, despite the potential negative implications on the incentives offered by §106 of the copyright act.

Note that fair use is an affirmative defense to a claim of copyright infringement. That is, even if a copyright holder can establish that a defendant infringed their copyright, if the defendant can show its use of the protected work is permitted under the fair use provision of the copyright act, the defendant will not be liable for copyright infringement. To help determine if a specific use of copyrighted material is permitted as a fair use, Congress has implemented a four-factor test in 17 U.S.C. § 107 to weigh the equity – fairness – of the use.

17 U.S.C. § 107 states, in relevant part:

Notwithstanding the provisions of §106 and §106(a), the fair use of a copyrighted work, including such use by reproduction in copies or phonorecords or by any other means specified by that section, for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship, or research, is not an infringement of copyright. In determining whether the use made of a work in any particular case is a fair use the factors to be considered shall include –

1. The purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

2. The nature of the copyrighted work;

3. The amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and

4. The effect of the use upon the potential market for, or value of, the copyrighted work.

Note that this is a factors test: that is, a court will consider each factor independently in order to weigh the overall equity in permitting the infringing use. Due to the subjective nature of each factor, along with their high degree of sensitivity to specific facts, it would take pages to summarize the way courts have come out on fair use analyses. I will not go into that much depth here, but here’s a little taste of what courts tend to look at when considering each factor.

Purpose and Character of the Use

Courtesy of Courtoons.com.

Arguably the most important factor in the fair use analysis is the purpose and character of the use of the work. In evaluating the use, “transformative” uses are more likely to weigh in favor of the would-be fair user while uses that are “derivative” are more likely to weigh against a fair use finding. Generally speaking, a work is transformative if it includes independent creativity by the would-be fair user, such as in a piece of criticism (where a copyrighted passage might be reproduced for purposes of analysis in the criticism) or a parody (where copyrighted material might be reproduced in order to comment on it).

For an interesting (and awkward…) discussion of the importance of this principle, check out Campbell v. Acuff-Rose, Music Inc., 510 U.S. 569 (1994), where 2 Live Crew’s parodic sampling of Roy Orbison’s Oh, Pretty Woman was determined to be a sufficiently transformative fair use of the original work.

Nature of the Copyrighted Work

Arguably the least important factor in the fair use analysis, here courts look to evaluate the degree of creativity of the copyrighted work. As such, fictional works generally weigh in favor of the copyright holder while non-fiction works are more likely to favor the would-be fair user (as Life Magazine found out…but I am getting ahead of myself).

Amount and Substantiality of Use

In evaluating this factor, courts look at both ‘how much’ and ‘what’ the would-be fair user has taken from the copyrighted work. Courts have run the gamut here, finding for a fair use defense even when a user has liberated all of a copyrighted work (see e.g. Kelly v. Arriba Soft Corporation, 280 F.3d 934 (9th Cir. 2002)) and against a fair use defense when the user took only a small piece of the copyrighted work (Harper & Row Publishers Inc. v. Nation Enterprises, 471 U.S. 539 (1985).

Overall, there are two primary considerations at play here. First, did the would-be fair user take as little of the copyrighted work as necessary to complete its own creative work? If so, it favors a finding of fair use. Secondly, did what was taken of the copyrighted work make up the “heart” (e.g. most powerful or interesting passages, the definitive quality of the copyrighted work, etc.) of it? If yes, courts tend to disfavor a fair use finding.

Effect of Use on Copyright Value

The final factor in the fair use analysis considers the effect the would-be fair use has on the market value of the original copyrighted work. If the fair use harms the market value of the original work, courts tend to disfavor the fair use, while if it has no impact – or increases – the value of the original, courts will generally favor a fair use determination. Note that while the later decided Campbell case (above) describes the primacy of the “purpose and character” of the use as a factor, earlier cases, such as Harper & Row, assert the primacy of the “Effect of Use” factor as the most important consideration.

Application of the Fair Use Defense

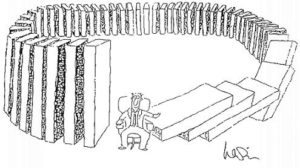

Reliance upon the fair use defense is problematic. Not only can evaluations of the different factors vary widely amongst different courts, but judges are given little guidance as to how the factors should be weighed against each other. What, for example, is a judge to do with a highly transformative parody, when the underlying copyrighted work was very creative, was copied in its entirety, and the parody significantly diminishes the commercial value of the underlying work? What about a work that is copied in its entirety, for purely commercial benefit by the would-be fair user, but where the work is minimally creative and the value for the underlying work is not harmed?

Reliance upon the fair use defense is problematic. Not only can evaluations of the different factors vary widely amongst different courts, but judges are given little guidance as to how the factors should be weighed against each other. What, for example, is a judge to do with a highly transformative parody, when the underlying copyrighted work was very creative, was copied in its entirety, and the parody significantly diminishes the commercial value of the underlying work? What about a work that is copied in its entirety, for purely commercial benefit by the would-be fair user, but where the work is minimally creative and the value for the underlying work is not harmed?

Unfortunately, given the subjective nature of the factors involved (e.g. How transformative is “enough”? What is the “heart” of the work? How creative, exactly, was the underlying work really?) and the factors’ sensitivity to specific fact patterns, fair use case law has a broad spectrum of results and is not very helpful, on the whole, either.

Ironically, the difficulties with the fair use defense were specifically addressed (intended?) by Congress as far back as 1967, when, in an impressively prescient analysis, the House Judiciary Committee noted that:

Although the courts have considered and ruled upon the fair use doctrine over and over again, no real definition of the concept has ever emerged. Indeed, since the doctrine is an equitable rule of reason, no generally applicable definition is possible, and each case raising the question must be decided on its own facts…the endless variety of situations and combinations of circumstances that can arise in particular cases precludes the formulation of exact rules in the statute.

Eventually the fair use doctrine was codified in the Copyright Act of 1976 (as 17 U.S.C. §107), but the concerns of House Judiciary Committee persist. As such, there will always be a degree of uncertainty whenever a fair use defense is in play.

Fair Use and the Zapruder Film

So how did the court find in favor of Thompson based on his fair use claim? You can find the court’s analysis in para. 131-4 of Time, Inc. v. Bernard Geis Assocs., but the following passage stands out in terms of illuminating the court’s thought process:

There is a public interest in having the fullest information available on the murder of President Kennedy. Thompson did serious work on the subject and has a theory entitled to public consideration. While doubtless the theory could be explained with [other non-infringing representations], the explanation actually made in the Book with copies is easier to understand. The Book is not bought because it contained the Zapruder Pictures; the Book is bought because of the theory of Thompson and its explanation, supported by Zapruder pictures.

In other words, the public’s interest in Thompson’s analysis of the work, enabled by his infringement of the frames of the Zapruder Film, outweighed Life’s interest in the copyright. Given Thompson’s financial interest in the infringement and the overall bad faith he showed in intentionally copying the frames, this certainly is an interesting outcome for an equitable doctrine – but it goes to show how perplexing the fair use doctrine can be.

So, given everything discussed above, the take-home message is this: when utilizing someone else’s copyrighted material, try to obtain permission first. If you do not, are sued, and are subsequently forced to assert a fair use defense, the only person who can be confident of a win will be your attorney.

If you have any questions or comments, please do not hesitate to contact the author or leave a comment below.

Join us next week when we discuss the implications of technology transfer.

|

About the Author

Bill Hadley, JD

|

Bill is a licensing associate at UNeMed, where he handles evaluation, development, marketing, and licensing for medical device, software, and telemedicine-based invention disclosures. He received a B.S. in Chemistry from the Colorado School of Mines and a J.D. from the Creighton University School of Law. Bill is currently in training for next fall’s intramural volleyball league, where he has personally guaranteed at least one victory for the mighty UNeMed Volley Llamas.

Contact Bill: Bill.Hadley@unmc.edu

|

Read article

The new Truhlsen Eye Institute is poised to revolutionize eye care in the region and will allow UNMC to join the ranks of other centers of excellence such as the Wilmer Eye Institute at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, and the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary at Harvard Medical School in Boston.

The new Truhlsen Eye Institute is poised to revolutionize eye care in the region and will allow UNMC to join the ranks of other centers of excellence such as the Wilmer Eye Institute at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, and the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary at Harvard Medical School in Boston. Through world-class research and patient care, UNMC generates breakthroughs that make life better for people throughout Nebraska and beyond. Its education programs train more health professionals than any other institution in the state. Learn more at unmc.edu.

Through world-class research and patient care, UNMC generates breakthroughs that make life better for people throughout Nebraska and beyond. Its education programs train more health professionals than any other institution in the state. Learn more at unmc.edu.

OMAHA, Neb. —

OMAHA, Neb. — “Intersect: Connecting Nebraska’s Startup Community” brings together innovators, investors and others to meet, mingle and share lessons learned. The conference will feature Startup Village, where entrepreneurs can showcase their ideas and products. The conference will also feature about 20 short presentations in a “

“Intersect: Connecting Nebraska’s Startup Community” brings together innovators, investors and others to meet, mingle and share lessons learned. The conference will feature Startup Village, where entrepreneurs can showcase their ideas and products. The conference will also feature about 20 short presentations in a “

As a licensing associate at UNeMed, it’s my job to

As a licensing associate at UNeMed, it’s my job to  Comprehending royalty distribution

Comprehending royalty distribution  Whereas research institutions may have different distribution percentages, each has a policy that dictates the distribution of revenues associated with technology license agreements. UNeMed is also responsible for managing the expenses and revenues associated with UNMC technology agreements.

Whereas research institutions may have different distribution percentages, each has a policy that dictates the distribution of revenues associated with technology license agreements. UNeMed is also responsible for managing the expenses and revenues associated with UNMC technology agreements. Once UNeMed receives the payment from the licensee, they first cover all costs incurred that are associated with the technology. Next, the inventor’s share is one third of the remaining revenue. The royalty payment check will arrive by mail to the inventor’s house and is subject to taxation as income.

Once UNeMed receives the payment from the licensee, they first cover all costs incurred that are associated with the technology. Next, the inventor’s share is one third of the remaining revenue. The royalty payment check will arrive by mail to the inventor’s house and is subject to taxation as income. OMAHA, Neb. (Feb. 13, 2013)—“Commercialize your technology: How to bring a product to market” is the title of the second talk given by Dr. Gary Madsen since joining UNeMed as Entrepreneur in Residence last June. His first talk, “What is an EIR and how can he help you” was given at this year’s Innovation Week and introduced the focus and goals of his new position.

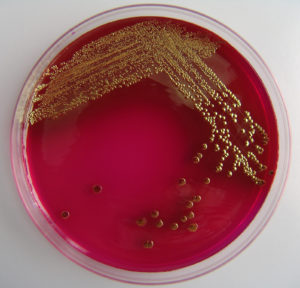

OMAHA, Neb. (Feb. 13, 2013)—“Commercialize your technology: How to bring a product to market” is the title of the second talk given by Dr. Gary Madsen since joining UNeMed as Entrepreneur in Residence last June. His first talk, “What is an EIR and how can he help you” was given at this year’s Innovation Week and introduced the focus and goals of his new position. Invention disclosures are the lifeblood of university technology transfer offices. Without an influx of quality inventions from faculty, graduate students, and other university employees, these offices would cease to exist. Unfortunately, what qualifies as a patentable invention – especially in the life sciences – can be difficult to understand. Indeed, it is my experience that many university research centers sit on a wealth of intellectual property that has never been disclosed for the simple reason that its creators never realized that they could obtain a patent on the results of their work.

Invention disclosures are the lifeblood of university technology transfer offices. Without an influx of quality inventions from faculty, graduate students, and other university employees, these offices would cease to exist. Unfortunately, what qualifies as a patentable invention – especially in the life sciences – can be difficult to understand. Indeed, it is my experience that many university research centers sit on a wealth of intellectual property that has never been disclosed for the simple reason that its creators never realized that they could obtain a patent on the results of their work. The first thing to note here is the term Processes

The first thing to note here is the term Processes  A U.S. patent court decision defined Compositions of Matter

A U.S. patent court decision defined Compositions of Matter

Reliance upon the fair use defense is problematic. Not only can evaluations of the different factors vary widely amongst different courts, but judges are given little guidance as to how the factors should be weighed against each other. What, for example, is a judge to do with a highly transformative parody, when the underlying copyrighted work was very creative, was copied in its entirety, and the parody significantly diminishes the commercial value of the underlying work? What about a work that is copied in its entirety, for purely commercial benefit by the would-be fair user, but where the work is minimally creative and the value for the underlying work is not harmed?

Reliance upon the fair use defense is problematic. Not only can evaluations of the different factors vary widely amongst different courts, but judges are given little guidance as to how the factors should be weighed against each other. What, for example, is a judge to do with a highly transformative parody, when the underlying copyrighted work was very creative, was copied in its entirety, and the parody significantly diminishes the commercial value of the underlying work? What about a work that is copied in its entirety, for purely commercial benefit by the would-be fair user, but where the work is minimally creative and the value for the underlying work is not harmed? Contrary to popular belief,

Contrary to popular belief,  Technology is typically transferred through a

Technology is typically transferred through a  The end goal of the commercialization strategy is to

The end goal of the commercialization strategy is to  A series of laws have been established to increase the technology transfer between federally-funded laboratories and nonfederal organizations while providing external entities with a means to access new technologies. Of these laws, the Bayh-Dole Act is credited for stimulating interest in technology transfer, as well as increasing research commercialization, educational opportunities, and economic development in the United States.

A series of laws have been established to increase the technology transfer between federally-funded laboratories and nonfederal organizations while providing external entities with a means to access new technologies. Of these laws, the Bayh-Dole Act is credited for stimulating interest in technology transfer, as well as increasing research commercialization, educational opportunities, and economic development in the United States. Technology is typically transferred through a

Technology is typically transferred through a  For this reason,

For this reason,

As discussed before,

As discussed before,  A third commercialization approach is for the rights holder to license the intellectual property to a third party. Intellectual property licensing is

A third commercialization approach is for the rights holder to license the intellectual property to a third party. Intellectual property licensing is