Bacterial infections are a glitch.

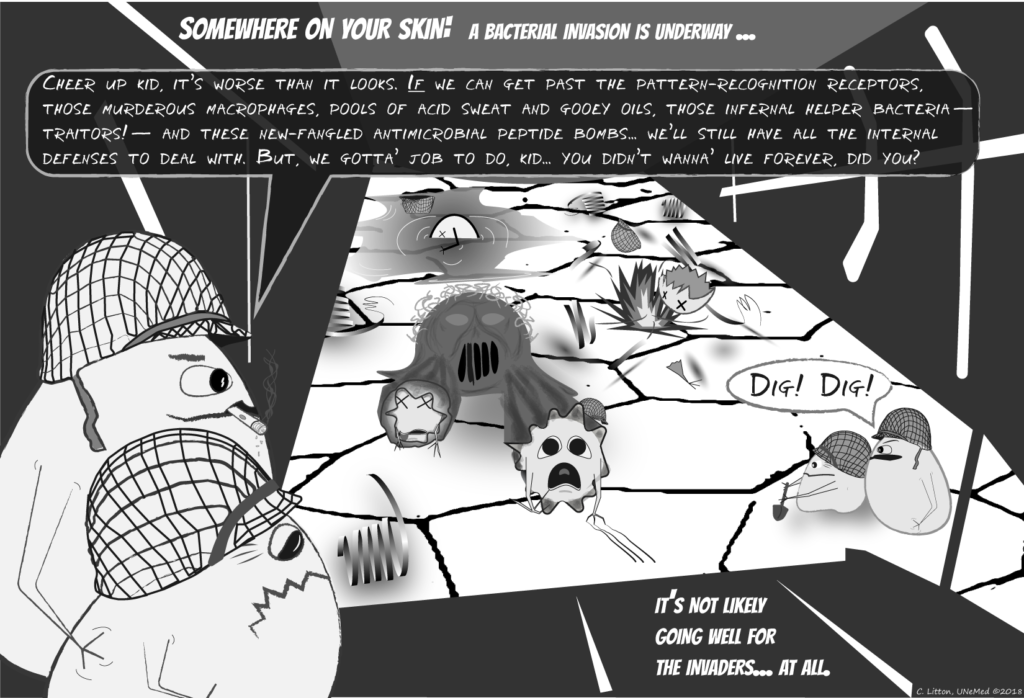

The marvel that is the human immune system keeps us safe from billions of microscopic organisms every day. Skin may not look like much more than a soft and fragile surface, but intact and healthy, it represents an impenetrable wall, equipped with security sensors, armed guards, and decked out in a variety of traps, snares and proximity mines for good measure.

Innate immunity is formidable: The result of an evolutionary arms race with pathogens that has spanned several hundred million years. The human immune system is really a combination of two overlapping systems: innate and adaptive immunities. While both are important, the ancient innate immune response is comprised of nonspecific defense mechanisms that form the first response to pathogens. Adaptive immunity is much more specific; it learns to specifically target pathogens we have already encountered and, therefore, are likely to encounter again.

Innate immunity is formidable: The result of an evolutionary arms race with pathogens that has spanned several hundred million years. The human immune system is really a combination of two overlapping systems: innate and adaptive immunities. While both are important, the ancient innate immune response is comprised of nonspecific defense mechanisms that form the first response to pathogens. Adaptive immunity is much more specific; it learns to specifically target pathogens we have already encountered and, therefore, are likely to encounter again.

Bacterial pathogens only stand a chance when things go wrong. And any medical procedure presents an opportunity for things to go wrong.

A breach in the skin—from a cut, for instance—creates the possibility for surrounding pathogens to enter the body. This is why, given the option, surgical procedures, like implanting a medical device, aren’t just performed anywhere. If cleanliness is next to godliness then the operating room is a holy temple. If bacteria get through that first line of defense, they can cause tissue or organ specific infections or even systemic infections with fatal outcomes.

Implanted medical devices are a double-edged sword, then. On one hand, they are a modern miracle of biomedical engineering; providing a synthetic solution where nature has failed. On the other hand, they represent a literal chink in the armor.

Implanted medical devices are a double-edged sword, then. On one hand, they are a modern miracle of biomedical engineering; providing a synthetic solution where nature has failed. On the other hand, they represent a literal chink in the armor.

For reasons that aren’t yet completely understood, opportunistic pathogens are highly attracted to these implanted medical devices. Once discovered, the bacterial invaders quickly go to work colonizing the implant until a mature community, or biofilm, is established.

If the bacteria are allowed to establish a biofilm, it has successfully beaten the immune response. About the only option left is to relinquish the territory and hopefully contain the bacteria to that one location in the body. And because antibiotics are impotent against bacterial biofilms, the only effective solution is total removal of the implanted device along with any infected surrounding bone and muscle tissue. If that doesn’t sound bad enough, the patient is also at a significantly increased risk for recurrent infection on any new device.

But if a medical device could be imbued with its own innate immunity, then the implant would be more like human skin. The implant could prevent bacterial attachment and inhibit biofilm formation.

Researchers have long been focused on discovering ways to prevent bacterial biofilm formation on medical devices by modifying the material surface properties. But what if the best solution is simply to think of the implant surface as an extension of the natural surfaces in our body? The first line of defense for these natural surfaces isn’t special patterning or unique physical properties, but innate immunity.

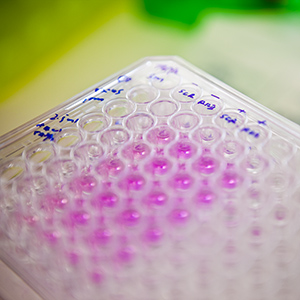

Guangshun Wang, PhD, at UNMC, has designed antimicrobial peptides to coat the surface of metallic orthopedic implants, and specifically target MRSA. Not only do these proteins prevent MRSA biofilm formation, but they also recruit host immune cells to help clear any opportunistic bacteria.

The preliminary data looks promising, with impressive effectiveness against MRSA biofilms. Dr. Wang is now seeking corporate partners to sponsor additional proof-of-concept research specifically focused on coating orthopedic implants. The hope is that by adding these peptides to the implant’s surface, Dr. Wang’s technology will effectively imbue the medical device with its own first line of defense.

[…] Skin holds off nearly all infections, but no match for biofilms An interesting blog post—and fun infographic—noting the skin’s remarkable ability to ward off […]