Read the original article here: https://www.omaha.com/article/20120223/MONEY/702239955

by Roger Buddenberg, Omaha World-Herald

OMAHA, Neb. (Feb. 20, 2012)—Connie Ryan was watching one of the “CSI” shows on television recently when she heard the investigator lament that a perp was likely to slip through the cops’ fingers because a tiny bit of DNA evidence would take hours — hours! — to analyze.

“I thought, we ought to call them,” she said. Because it shouldn’t take that long anymore.

Her Omaha company, Streck Inc., has just brought to market a laboratory device that dramatically speeds up the task. More important, the gizmo was invented, developed into a salable product and built in Nebraska — an example, Ryan said, of the kind of homegrown inventor-entrepreneur collaboration that can rev up the state’s economy, create jobs and even revive America’s beleaguered manufacturing sector.

She thinks that’s a message Nebraska’s policy makers and its wealthy — its would-be venture capitalists — ought to hear.

But first the device. It’s called a thermal cycler.

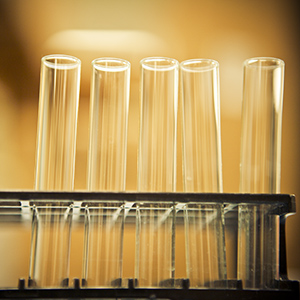

It can rapidly and precisely heat and cool a minute trace of DNA — a fleck of blood or a snippet of virus — thus multiplying it through a process called polymerase chain reaction so that it’s big enough to be analyzed. This copying process is a quarter-century old, but until now has taken an hour or two per batch.

That’s fine if you’re not in a hurry.

But if you are, say, a cop tracking a murderer or a hospital rushing to diagnose a lethal disease or to see whether perishable transplant tissue is compatible — speed is vital, Ryan said. Her company’s machine, called the Philisa Thermal Cycler, cuts the time to 15 minutes.

The first Philisa has just been sold for about $10,000 to a government agency that wants to remain anonymous because it is about to publish research involving the machine, Ryan said. About a dozen other Philisas are getting tryouts with hospitals and other potential customers.

The goal, she said, is to sell 50 in the next six months. And she’s confident, based on Streck’s 41-year track record of identifying the lab problems of the white-coated crowd, then devising solutions for them.

Getting to this point, though, wasn’t simple. And Ryan thinks the tale holds some lessons:

The idea for the speedier thermal cycler was born about eight years ago with three University of Nebraska-Lincoln academics, Hendrik Viljoen, a professor of chemical biomolecular engineering, and two colleagues, Joel TerMaat, then a doctoral candidate, and Scott Whitney, then a post-doctoral fellow.

They formed a company, but it was little more than an idea worked out in a Lincoln garage using cobbled-together materials such as drinking straws from a nearby 7-Eleven, Viljoen said.

What it needed, Ryan said, was someone with money and the know-how to turn the idea into a marketable product. That’s where Streck came in. It bought the startup in March 2010, put TerMaat and Whitney on the payroll and hired Viljoen as a consultant.

Playing matchmaker for this deal were two arms of the university devoted to commercializing scholars’ ideas, NUtech Ventures and UNeMed, as well as a member of Nebraska Angels, a group that investigates early-stage investment opportunities.

One more ingredient was required to make the device a practical reality, Ryan said: plastic tubes of just the right shape and thickness to hold the DNA samples. After all, you can’t keep using straws from the 7-Eleven.

Again, a Nebraska company filled the bill, she said. Streck turned to HTI Plastics, an injection-molding firm founded in Lincoln in 1985.

“People sometimes underestimate the technology that exists in this state,” Ryan said. “We really have some amazing companies.”

What’s necessary to replicate this story, she said, is more money, nerve and entrepreneurial know-how.

The ideas are plentiful — “there are tons of interesting things happening at our universities,” she said.

And so is the money. “We have a lot of wealthy people in this community. . I think wealthy people want to make a difference. Investing in our state is a great way.”

Facilitators can help, such as UNL’s Innovation Campus, now taking shape on the former state fairgrounds, she said.

But the real shortage, she said, is entrepreneurial — people able to sift through ideas, pick ones that are good risks, then put in the money and hard work needed to turn them into market-worthy products. And good Nebraska manufacturing jobs.

Contact the writer: 402-444-1140, roger.buddenberg@owh.com

Read the original article here: https://www.omaha.com/article/20120223/MONEY/702239955