by Bill Hadley, UNeMed | Feb. 5, 2013

Invention disclosures are the lifeblood of university technology transfer offices. Without an influx of quality inventions from faculty, graduate students, and other university employees, these offices would cease to exist. Unfortunately, what qualifies as a patentable invention – especially in the life sciences – can be difficult to understand. Indeed, it is my experience that many university research centers sit on a wealth of intellectual property that has never been disclosed for the simple reason that its creators never realized that they could obtain a patent on the results of their work.

Invention disclosures are the lifeblood of university technology transfer offices. Without an influx of quality inventions from faculty, graduate students, and other university employees, these offices would cease to exist. Unfortunately, what qualifies as a patentable invention – especially in the life sciences – can be difficult to understand. Indeed, it is my experience that many university research centers sit on a wealth of intellectual property that has never been disclosed for the simple reason that its creators never realized that they could obtain a patent on the results of their work.

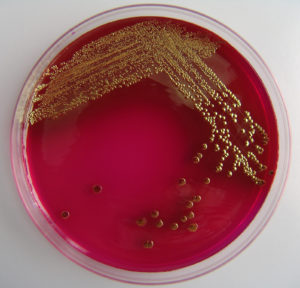

To illustrate the complexity of this issue, take the curious case of Ananda Mohan Chakrabarty. In 1971, Chakrabarty, then working for General Electric, developed bacteria capable of metabolizing crude oil. The bacteria quickly garnered widespread acclaim for its ability to mitigate the damage caused by oil spills. Noting that no naturally-occurring bacteria possessed this property, Chakrabarty and GE applied for a patent.

Consider that for a moment. In effect, Chakrabarty had created a new life form that had never existed in nature, and had the audacity to attempt to patent – monopolize! – the rights to that lifeform.

While the ethical and political ramifications of Chakrabarty’s patent application are staggering, the pertinent question for our purpose is much simpler: “Can you even patent that?” This is, hopefully, the same question many researchers have about their own research. So, without further ado, let’s take a closer look at the types of inventions that are eligible subject matter for patent protection.

The Patent Act of 1952 lists four categories of patentable subject matter for a utility patent:

- Processes

- Machines

- Manufactures, or “Articles of Manufacture”

- Compositions of Matter

Additionally, any improvement to an existing invention in one of these fields is eligible for patent protection. These terms are ambiguous so let’s take a closer look at each to sort them out.

Processes

The first thing to note here is the term Processes also includes methods. Process patents can become complex when discussing things like software patents or business method patents. But for most purposes, a process is generally thought to be intended to cover things like manufacturing processes which is a series of steps to make something.

The first thing to note here is the term Processes also includes methods. Process patents can become complex when discussing things like software patents or business method patents. But for most purposes, a process is generally thought to be intended to cover things like manufacturing processes which is a series of steps to make something.

A method generally refers to a specified way of using something.

Thus, a description of a series of steps to cure rubber might be a process, while a method might comprise the steps of a specified administration of a therapeutic agent to treat a condition.

Machine

A Machine can be thought of as a concrete thing, consisting of parts, or of certain devices and combinations of devices. This includes mechanical devices, or combinations of mechanical powers and devices to perform some function and produce a certain effect or result. So, a machine may be something like a carburetor, a laser, or a photocopier – devices that autonomously perform a function utilizing a system, or systems, of mechanical devices.

Manufactures

Manufactures, also called Articles of Manufacture, are tangible items or commodities, such as ceramics, alloys, or simple tools.

Patentable Subject Matter

A U.S. patent court decision defined Compositions of Matter as “all compositions of two or more substances and all composite articles, whether they be the results of chemical union, or of mechanical mixture, or whether they be gases, fluids, powders, or solids.” Put another way, a composition of matter is, essentially, any tangible “thing” which is formed by the combination of two or more components, and which possesses properties belonging to neither parent component in each parent component’s individual capacity.

A U.S. patent court decision defined Compositions of Matter as “all compositions of two or more substances and all composite articles, whether they be the results of chemical union, or of mechanical mixture, or whether they be gases, fluids, powders, or solids.” Put another way, a composition of matter is, essentially, any tangible “thing” which is formed by the combination of two or more components, and which possesses properties belonging to neither parent component in each parent component’s individual capacity.

Inventions Not Eligible for Patent Protection

Interestingly, just as there are certain statutorily defined categories of patentable subject matter, certain types of inventions are excluded from patent eligibility. These excluded inventions include:

- Any strategy for reducing, avoiding, or deferring tax liability.

- A naturally-occurring organism.

- A human or anything encompassing a “human organism”, per se.

- A computer program, per se.

- Surgical Methods – sort of. In fact, it is possible to obtain a patent on a surgical method, but the claims of any allowed patent are essentially unenforceable.

- Any invention whose only use pertains specifically to atomic weapons.

- Natural phenomena, mathematical equations, mental processes, and similar abstract intellectual concepts. Note that while such conceits are not patentable, certain methods or processes which utilize them may be, if those patents do not claim the concept itself.

A Patent for Chakrabarty’s Invention

The controversy over the patentability of Chakrabarty’s organism reached the Supreme Court in 1980. The court first noted that there was no obvious congressional intent to disavow living organisms as patentable subject matter, noting that “Congress thus recognized that the relevant distinction was not between living and inanimate things, but between products of nature, whether living or not, and human-made inventions…”.

Thereafter, the only remaining issue for the court to determine was whether Chakrabarty’s organism fell into one of the four specified categories. This, in turn, boiled down to whether the organism was an article of manufacture, a composition of matter, or neither. In evaluating this question, the court reasoned that:

[Chakrabarty’s] claim is not to a hitherto unknown natural phenomenon, but a non-naturally occurring manufacture or composition of matter – a product of human ingenuity ‘having a distinctive name, character and use’…[Chakrabarty] has produced a new bacterium with markedly different characteristics from any found in nature and one having the potential for significant utility. His discovery is not nature’s handiwork, but his own; accordingly it is patentable subject matter under §101.

The court does not, of course, specify which category Chakrabarty’s organism falls into – that would be entirely too helpful.

So, if the Supreme Court of the United States is unable to accurately figure out how to classify these things, what is a simple researcher to do? My advice?

If you have any questions or comments, please do not hesitate to contact the author or leave a comment below.

Join us next week when we discuss the Royalty Distribution.

|

About the Author

|

Bill has ample experience handling evaluation, development, marketing, and licensing for medical device, software, and telemedicine-based invention disclosures. He received a B.S. in Chemistry from the Colorado School of Mines and a J.D. from the Creighton University School of Law. Contact Bill: whadley14@gmail.com |